A short video by Cameroonian content creator Real Nsoh Nde recently reignited an uncomfortable conversation: why do some people of African descent, across Europe, North America, South America, and even Africa itself, refuse to identify as Black? Why do some light-skinned or mixed-race individuals distance themselves from darker Africans? And why do so many young Africans migrate westward not only for economic opportunity, but with an underlying belief that value, prestige, and excellence exist elsewhere?

It is a painful question: Do Africans hate being African?

The short answer is no. But the longer answer is more complex—and more urgent.

The Colonial Inheritance: Identity Under Pressure

For centuries, Africa was not only colonized politically and economically; it was colonized psychologically. European colonial systems reshaped education, religion, language, and cultural aspirations. Generations grew up learning more about European monarchs than African empires, more about foreign wars than African resistance movements, and more about foreign literature than African storytelling traditions.

This is not accidental. Cultural theorists call it soft power, the ability of nations to influence others through culture, media, and ideas. When African children grow up watching American superheroes, Japanese anime, French television, and British dramas, while rarely seeing high-quality content from their own communities, the subconscious message is clear: value comes from elsewhere.

This does not mean Africans consciously hate themselves. But it does suggest that perception has been shaped externally for decades.

Migration and the Mirror of Worth

Economic migration from Africa to Europe and North America is often framed purely as a search for opportunity. And yes, structural inequalities, unstable economies, and governance challenges drive many to leave. But economic decisions are never entirely separate from identity.

When success is consistently portrayed as something achieved “abroad,” the continent itself begins to feel like a temporary waiting room. The “land of the colonizer” becomes not just a place of financial advancement, but of perceived validation.

This is where the inferiority complex can quietly take root.

It manifests subtly:

– Distancing oneself from “African” identity abroad.

– Preferring Western aesthetics over African ones.

– Consuming foreign media while dismissing local productions.

– Associating excellence with foreign validation.

Not everyone feels this way. In fact, many Africans across the diaspora are actively reclaiming pride in African identity. But the fracture is visible enough to warrant reflection.

The Creative Industry as a Battleground

Nowhere is this tension clearer than in the comics and animation space.

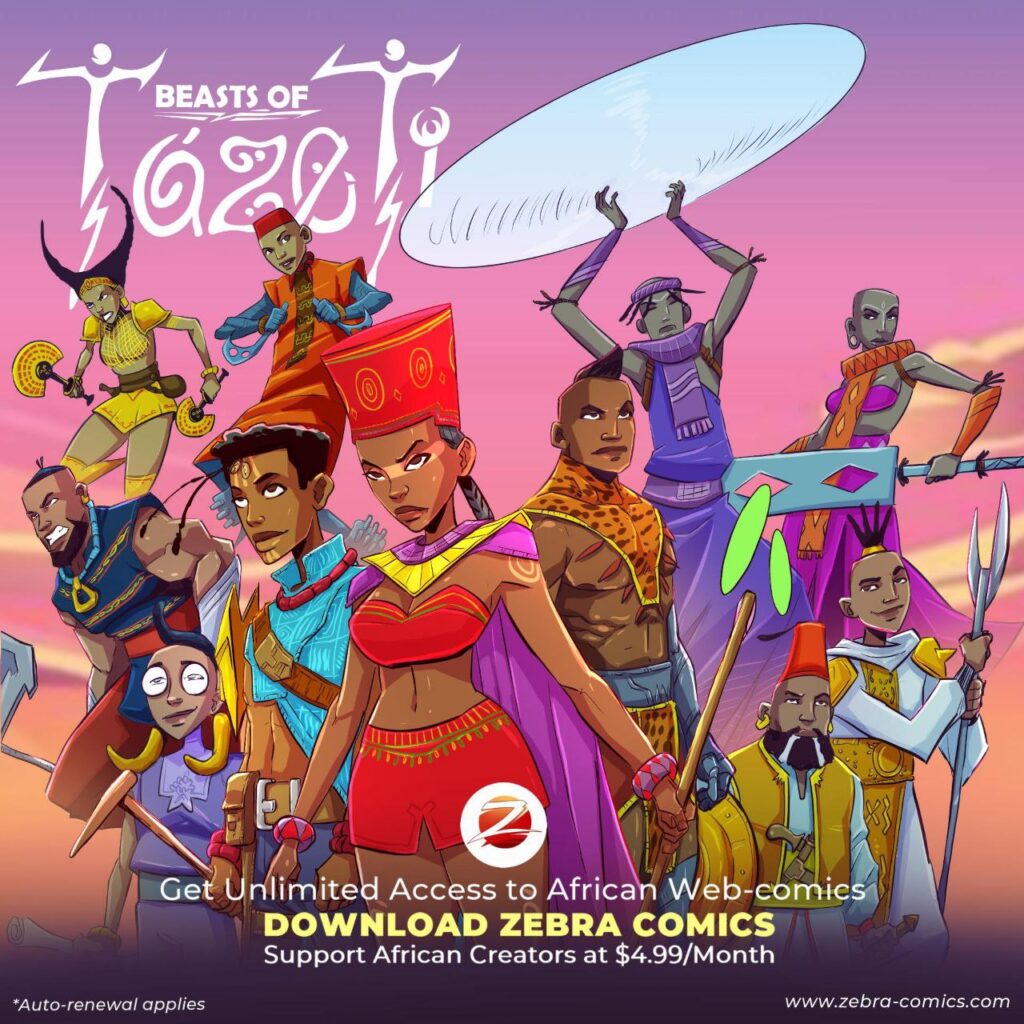

Across the continent, creators are building incredible worlds, rooted in African mythology, modern urban realities, futuristic Afro-centric visions, and hybrid storytelling. Platforms producing African Comics and Webcomics are growing. Independent artists are crafting IPs that rival global standards in quality and imagination.

Yet many African fans still default to Japanese manga or American superhero comics.

The excuse?

“They’re more mainstream.”

“They’re more interesting.”

“They’re better produced.”

But notice the phrase often used: “what we are used to.”

That familiarity was built over decades. Japanese manga did not become dominant overnight. American comics were not always global giants. Both industries were supported domestically long before they were exported internationally. Their local audiences chose them—even when they were imperfect.

African creators rarely receive the same grace period.

If the story references tradition, some say it is “too tribal.”

If it shows a modern Africa, some say it is “trying too hard.”

If it experiments with Afro-futurism, some call it unrealistic.

The truth? The issue is less about quality and more about perception.

Otakus and the Global Imagination

Let’s address a sensitive topic: the global rise of anime fandom.

Anime culture is powerful. Japan invested heavily in storytelling as national export. Young Africans who grew up watching Naruto, Dragon Ball, or One Piece developed emotional connections to those worlds. That attachment is real and meaningful.

But when admiration becomes exclusive loyalty—when anything local is dismissed before engagement—that signals a deeper imbalance.

This is not the fault of fans alone. Governments across Africa have historically underfunded creative industries. Policies supporting animation studios, comic publishers, and transmedia storytelling remain minimal. Grants, subventions, and soft power strategies are inconsistent.

While other countries trained their youth through cultural storytelling, Africa largely outsourced imagination.

And imagination shapes identity.

Do Africans Hate Africa?

No. But some have internalized narratives that diminish Africa.

Colorism within communities—where lighter skin is sometimes privileged socially—reflects colonial beauty hierarchies. Disassociating from “Blackness” abroad often stems from a desire to avoid discrimination in societies where Blackness has been marginalized.

These are survival strategies shaped by history.

But survival is not the same as pride.

Across fashion, music, literature, and cinema, there is also a massive counter-movement reclaiming African excellence. Nollywood, once mocked for its low budgets, is now one of the largest film industries globally. Afrobeats dominates international charts. African fashion designers are reshaping global runways.The same renaissance is happening in African Comics and Webcomics, but it requires deliberate audience support.

Representation as Lifeline

For young Africans, seeing themselves as heroes matters.

It matters to see cities that look like Douala, Lagos, Nairobi, or Johannesburg rendered in epic panels.

It matters to see African mythology adapted into futuristic sagas.

It matters to see characters who look like them solving global crises.

Stories are not just entertainment. They are identity reinforcement systems.

If children grow up anchored in narratives where Africans are protagonists—not side characters—they internalize confidence.

This does not mean applauding poor quality. Standards must remain high. Constructive criticism is necessary. But local industries need audience space to grow. Japan protected its manga market before it conquered the world. America nurtured its comic book industry long before Marvel became a cinematic empire.

African creative industries deserve the same incubation.

The Psychological Shift Required

The real question is not “Do Africans hate being African?”

It is: Have Africans been trained to undervalue their own cultural production?

When people say African stories are “not mainstream,” they reveal the benchmark they are using. Mainstream by whose standard? Western media algorithms? International licensing networks? Or local impact?

Mainstream status is built, not inherited.Choosing local content—especially in African Comics and digital Webcomics—is not charity. It is investment in narrative sovereignty.

A Future Built on Cultural Confidence

The 21st century is not only about economic competition. It is about cultural influence.

If Africa does not shape its own stories, someone else will shape them.

The next generation of African creators—writers, illustrators, animators—are ready. What they need is consistent ecosystem support: audience engagement, policy backing, and industry infrastructure.

Because identity is not just about pride—it is about power.

And storytelling is one of the most powerful tools of all.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Do Africans hate being African?

No. While some individuals may struggle with identity due to historical and social influences, the majority of Africans express pride in their culture and heritage. The tension often reflects colonial legacy, colorism, and global media influence rather than self-hatred.

2. Why do some Africans prefer foreign media over African content?

Decades of exposure to Western and Asian media created familiarity and emotional attachment. Limited government support for local creative industries also slowed the growth of competitive African media ecosystems.

3. Are African Comics growing globally?

Yes. African Comics and Webcomics are rapidly expanding, especially through digital platforms. African mythology, Afro-futurism, and modern urban narratives are gaining traction both locally and internationally.

4. How does media influence African identity?

Media shapes perception. When young Africans primarily consume foreign content, it can influence how they view success, beauty, heroism, and cultural value. Balanced representation strengthens identity confidence.

5. What can be done to strengthen African creative industries?

– Increased government policy support and funding

– Private investment in animation and comics studios

– Audience engagement with local Webcomics

– Education reforms that include African history and literature

– Cross-continental collaboration among creators

Africa does not hate itself.

But healing perception fractures requires intentional effort—through education, policy, and especially storytelling.

Because when Africans control their narratives, they control their future.